AI Will Take Your Job (And That's The Economic Reality)

I’ve been reading Henry Ford’s My Life and Work lately, and there’s something about his relentless focus on economic efficiency that keeps nagging at me. Ford wasn’t sentimental about the old ways. He saw the math and followed it wherever it led, even when it meant upending entire industries.

That same calculating perspective has been haunting my thoughts about AI and software engineering.

I imagine the horse breeders had a good laugh when Ford unveiled his Model T in 1908. “A horseless carriage? Preposterous!” they must have chuckled, watching this contraption sputter and cough its way down the road. After all, horses were reliable, understood, and had powered transportation for millennia. Surely this noisy mechanical beast was just a passing fad.

The horse breeders weren’t stupid: they were operating on perfectly sound logic based on everything they knew. Horses were better in many ways: they could navigate rough terrain, didn’t need gas stations, and required no mechanical expertise to operate. But they missed one critical variable in their calculations: economics.

The Model T wasn’t better because it was more elegant or more capable in every scenario. It won because Ford made it cheap enough that the math simply couldn’t be argued with. When you could produce and maintain an automobile for a fraction of what it cost to breed, feed, and stable horses at scale, the game was over. The horses didn’t lose on merit; they lost on cost per mile.

The Uncomfortable Truth

I was wrong.

For months I was one of those well-intentioned voices saying, “AI won’t replace engineers, it’s just a tool to augment us.” I wanted to believe it. I still want to believe it. But after spending substantial time building with AI-assisted coding tools like Warp, I can no longer ignore the economic reality staring me in the face.

Anyone who claims AI won’t replace engineers in most tasks, though well-intentioned, is completely wrong.

Today, even in its crudest form, and make no mistake, AI-assisted coding is still in its infancy, I’ll take the code AI-assisted coding produces way more than hiring a junior engineer.

Not because I enjoy replacing humans with machines, but because it’s so cost-effective that ignoring this reality would be a disservice to anyone trying to build something sustainable while keeping cost low.

So yes, you should be worried if all you can do is write mediocre code, because I can use AI for that and teach it to produce what I consider good enough code in half the time I can teach a junior human engineer. And that’s not opinion—that’s just math and math don’t lie.

It’s Not About Being Better, It’s About Being Cheaper

Here’s what most people miss in this debate: AI doesn’t have to be better than you at everything. It just has to be cheaper at enough things.

A junior engineer might cost me $50,000-$80,000 annually (and that’s being conservative in many markets). They need benefits, time off, sick days, and most importantly, months of onboarding before they become productive. They’ll write bugs (we all do), need code reviews, require mentorship, and occasionally have a bad day where their output drops to zero.

AI-assisted coding, on the other hand, costs me somewhere between $20-$200 monthly depending on the tooling. It doesn’t sleep, doesn’t need health insurance, never asks for a raise, and doesn’t require months of domain knowledge transfer. When it produces bad code, I reject it and ask it to iterate on it again and again until the output match my tastes. No hurt feelings, no morale issues.

The economic argument isn’t even close.

The Work That Still Remains Human

Now, before you think I’m advocating for a world where we fire all junior engineers and replace them with Warp, Claude Code, or any other AI-assisted coding tools, let me be clear: there are things AI still can’t do well… yet.

AI struggles with:

- Architectural decisions that require understanding long-term business strategy

- Debugging complex, gnarly systems with layers of context and historical decisions

- Asking the right questions when requirements are vague or political

- Having taste about what “good enough” actually means for your users

- Navigating human dynamics in code reviews and technical discussions

These are the skills that still make senior engineers valuable. These are the moats that won’t be easily crossed by probabilistic token prediction.

”But AI Isn’t Creative!”

I hear this argument often: “AI can’t be creative. That’s what makes human engineers irreplaceable.”

I want to believe this. It’s comforting. But I’ve watched AI suggest architectural approaches I hadn’t considered, combine patterns in novel ways, and propose solutions that made me think, “Huh, that’s actually clever.”

The uncomfortable truth? AI can be creative. It can generate original solutions, make unexpected connections, and produce ideas that feel genuinely inventive.

What AI struggles with isn’t creativity itself. It’s knowing which creative solution is right. It can generate ten clever approaches to a problem, but it can’t tell you which one fits your team’s skill level, your technical debt situation, your timeline, and your users’ actual needs.

That judgment, that taste, that’s what still makes engineering beautiful and human. Not the ability to think of solutions, but the wisdom to choose the right one.

But here’s the uncomfortable part for senior engineers: AI is in its earliest, crudest version right now.

Don’t rest on your laurels thinking these higher-order skills are permanently safe. I’ve experienced firsthand that I can already have meaningful architecture discussions with AI today and get good enough output to work with. Not perfect, not always right, but good enough to be useful.

If AI can already participate in architecture conversations in 2025, what will it be capable of in 2027? 2030? The moat you’re relying on might be shallower than you think.

The senior engineers who will survive aren’t those banking on AI never catching up: they’re those who keep pushing further ahead, always staying beyond whatever AI can currently do.

But let’s be honest: most junior engineering work doesn’t involve these higher-order skills. Most junior work is implementing straightforward features based on clear requirements, fixing obvious bugs, and writing the kind of CRUD operations we’ve all written a thousand times.

And that’s precisely the work AI already does well enough.

The Mediocre Code Problem

There’s a phrase that’s been haunting me: mediocre code.

What do I mean by mediocre code? Code that works (mostly), follows some conventions (kind of), and gets the job done (eventually). It’s not elegant, it’s not particularly maintainable, and reading it won’t teach you anything new. But it runs, passes basic tests, and ships features.

Mediocre code is what most junior engineers write, not because they’re bad engineers, but because they’re learning. We all wrote mediocre code when we started. I certainly did. It’s part of the journey.

The problem is, from a business perspective, I don’t need to nurture that journey if I can get the same mediocre output immediately. And that’s where AI has become devastatingly effective.

I can prompt an AI with “build a REST API for user authentication with password reset functionality” and get mediocre-but-working code in minutes. Sure, I’ll need to review it, probably refactor some parts, and definitely test it. But that’s still faster and cheaper than hiring someone to write that same mediocre code over the course of days or weeks while they learn our codebase.

The uncomfortable truth is: if your competitive advantage as an engineer is that you can write code that works, you don’t have a competitive advantage anymore.

The New Engineering Landscape

So what does this mean for engineers, especially those starting out?

The bar has moved. Dramatically.

Being able to “code” is no longer enough. It’s becoming table stakes, a commodity skill that AI can replicate cheaply. The engineers who will thrive in this new landscape are those who can:

- Supervise and direct AI effectively - Knowing what to ask for and how to evaluate what you get back

- Architect systems that AI isn’t sophisticated enough to design

- Make taste judgments about quality, performance, and user experience

- Debug complex systems by reasoning about behavior AI can’t see

- Communicate effectively with non-technical stakeholders to understand real requirements

- Think about second and third-order consequences of technical decisions

Notice what’s not on that list? “Write CRUD endpoints.” “Build form validation.” “Implement authentication.” These are all things AI can do well enough, today, in its crude form.

What You Should Do About This

If you’re a junior engineer or aspiring to become one, here’s my honest advice:

Don’t compete with AI on the things AI is good at. You won’t win on cost, and increasingly you won’t win on speed either.

Instead, focus maniacally on developing the skills AI can’t replicate:

- Deep debugging and system thinking

- Taste and judgment about software quality

- Communication and requirement gathering

- Strategic technical decision-making

And most importantly: learn to use AI as a force multiplier. The engineers who will succeed aren’t those who ignore AI, but those who wield it effectively to 10x their output.

Use AI to handle the boilerplate. Use it to generate test cases. Use it to explain unfamiliar codebases. But spend your actual cognitive energy on the problems that require human judgment and creativity.

The Quality of AI Code Depends on You

Here’s something that gets lost in the “AI will replace us all” panic: using AI to code feels natural because it is coding.

You’re still providing instructions to a computer, just in natural language instead of JavaScript or Python. It’s a different interface to the same fundamental activity: telling a machine what to do.

And here’s the kicker: just as there has always been good code and bad code, AI-assisted coding will also yield good and bad outcomes. The difference? It all hinges on the skill of the coder.

A mediocre engineer will produce mediocre prompts and get mediocre AI-generated code. A skilled engineer will craft precise requirements, spot issues in generated code, know when to accept or reject suggestions, and iterate until the output meets their standards.

A quick note: Using AI-assisted coding doesn’t mean “vibe coding” where you accept whatever comes out and ship it. The engineers actually thriving with AI-assisted coding are those who can get output quickly for their ideas and iterate faster than they ever could without it. They’re not coding less rigorously; they’re coding more rapidly, with tighter feedback loops and faster iteration cycles. The discipline remains; the velocity increases.

So I admonish coders to learn and get better at coding—not despite AI, but because of it. The better you understand software architecture, design patterns, edge cases, and code quality, the better you’ll be at producing high-quality AI-assisted code.

The skill hasn’t become obsolete. The medium has just evolved.

Go Deep: The T-Shaped Engineer Advantage

But what exactly should you study? What separates someone who can use AI to produce mediocre code from someone who can direct it to produce excellent solutions?

Study your craft deeply. Not just syntax and frameworks, but the fundamentals that make quality software:

- What makes code maintainable vs. code that technically works?

- Why do certain architectural patterns exist and when should they be applied?

- How do you balance performance, readability, and time-to-market?

- What are the trade-offs between different approaches to solving the same problem?

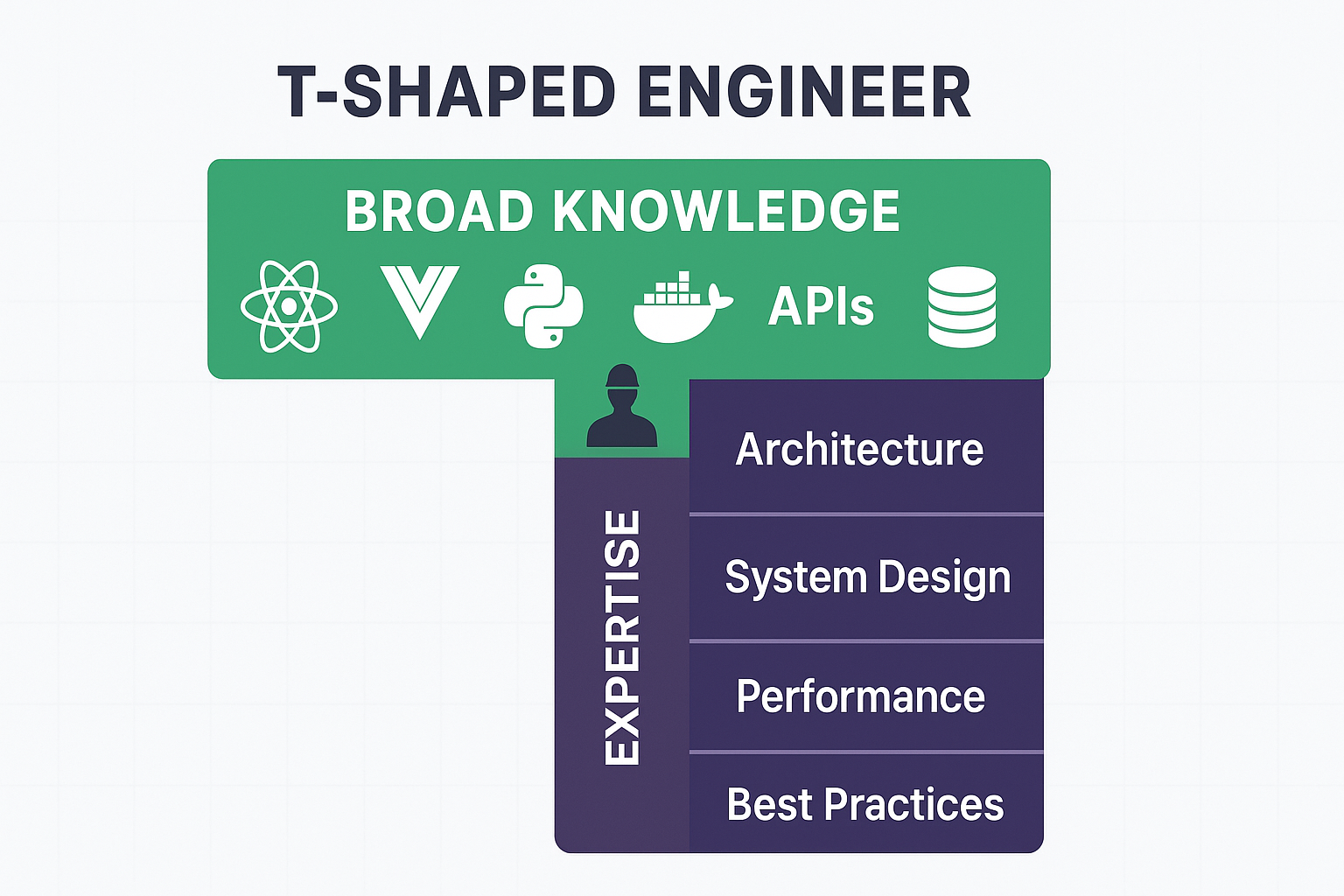

This is where the concept of the T-shaped engineer becomes critical. You need broad knowledge across the stack (the horizontal bar of the T), but you also need to go deep in at least one area (the vertical bar).

AI can give you breadth. It can explain React, then Vue, then Svelte all in the same conversation. But depth, true mastery of what makes software good rather than just functional, that’s what separates engineers AI can replace from engineers AI amplifies.

When you understand why certain patterns work, you can guide AI toward solutions that aren’t just correct, but elegant, maintainable, and aligned with long-term system health. When you only know surface-level “how-to,” you’ll accept whatever AI gives you, unable to distinguish good from good-enough from technical debt in disguise.

The Model T Didn’t Kill Transportation Jobs

Here’s something interesting about the Model T: it didn’t actually eliminate transportation jobs. It transformed them.

Horse breeders became obsolete, yes. But the automobile industry created mechanics, drivers, traffic engineers, auto designers, and entire supply chains that employed far more people than the horse industry ever did.

The people who suffered weren’t those who lost jobs. New jobs emerged. The people who suffered were those who refused to adapt, who insisted on breeding horses when the world had moved on.

AI will likely follow a similar pattern. Junior engineering jobs as we know them? Those may largely disappear. But new roles will emerge, roles we can’t fully envision yet, that require human judgment working in concert with AI capabilities.

The question is: will you be someone who adapts to this new reality, or will you insist on breeding horses?

The Economics Won’t Care About Your Feelings

I want to end with the hardest truth of all: the economics of this won’t care about our feelings.

I genuinely wish we lived in a world where companies hired junior engineers for their potential, gave them time to learn, and valued the human element of code. And some companies will continue to do that—but they’ll be competing against companies that use AI to move faster and cheaper.

When a startup can build their MVP with two senior engineers and AI assistance instead of needing a team of six that includes juniors, that’s what they’ll do. When a consultancy can deliver projects 40% faster and 60% cheaper by augmenting their seniors with AI instead of hiring more juniors, that’s the business they’ll run.

This isn’t about being cruel. It’s about survival in a competitive market. The horse breeders weren’t defeated by malice—they were defeated by math.

My Hope

Despite everything I’ve written here, I’m not pessimistic about the future of engineering. I’m just being realistic about the present.

The engineers who will thrive are those who see AI as a calculator, not a threat. When calculators arrived, we didn’t lament the loss of human computers—we celebrated that mathematicians could now focus on higher-order problems.

AI-assisted coding is the same. It’s freeing us from the drudgery of writing boilerplate so we can focus on architecture, strategy, and creativity.

But that transition requires honesty about where we are. And where we are is this: if you can only write mediocre code, AI is already better at that job than you are, and it costs a fraction of your salary.

The question isn’t whether AI will take your job. The question is: are you building skills that go beyond what AI can do cheaply?

Because the economics won’t wait for you to figure it out.

Code strategically 🎯,

Kelvin

What’s your take on AI replacing junior engineering work? Let me know on X/Twitter.